GESTALT and SUCCESSIVE APPROXIMATION in the "real world"

/The other day Turff (Chief Engineer of the GALAXY Project) texted me with images of some text from a book he was reading about leadership/coaching: The Coaching Habit: say less, ask more & change the way you lead forever, by Michael Bungay Stanier.

I ordered a copy and am halfway through it. It’s a quick read and really does provide seven key questions for managers who need better coaching skills, so I recommend it for anyone who has to manage other people.

Here is the passage Turff highlighted:

“The first paper […] cited has held up for more then eight-five years since it was published in 1929. The study found that when students were offered a second pass at a number to true-or-false questions, the “deliberate reconsideration” helped students get more answers correct. These students performed better than a second set, who also got a second pass but didn’t write down their answers during the first pass. This group performed worse than the first set of students so it seems that committing to an answer and then having a chance to reflect on it creates greater accuracy. More recent students have found that follow-up questions that promote higher-level thinking (like “And what else?”) help deepen understanding and promote participation.” [The Coaching Habit, p.71]"

The point is that all processes benefit from the ABORTIVE ATTEMPT > GESTALT > SUCCESSIVE APPROXIMATION cycle, not just our scribbling and doodling. Remember the Lyles Theorem of Process Development? “It takes three cycles of any process to get the process right.” I formulated that as the assistant program director for instruction of the Georgia Governor’s Honors Program: faculty dorm issues, classroom key distribution, internet access — a host of tasks that had to be dealt with, and it took me three summers to get it all sorted out. (And improved.)

The fact that the study cited dealt with students’ ability to get more right answers upon reflection made me think that our classrooms might be restructured to take advantage of Lichtenbergian principles.

This is not new, of course. All the research and discussion of “brain-based learning” back in the 90s showed us that the way learners construct knowledge is messy and non-linear — and of course our classrooms are almost always rigid and linear.

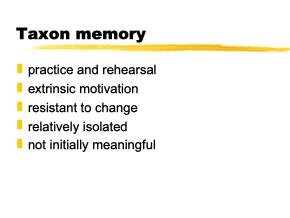

Quick sidebar: There are two kinds of memory, taxon and locale. Taxon memory is basically memorization, and it’s hard. The brain resists learning this way; it’s like scratching letters into rock. Very hard to do, but once it’s in there, it’s there pretty permanently. (Quick: what’s 7x8?)

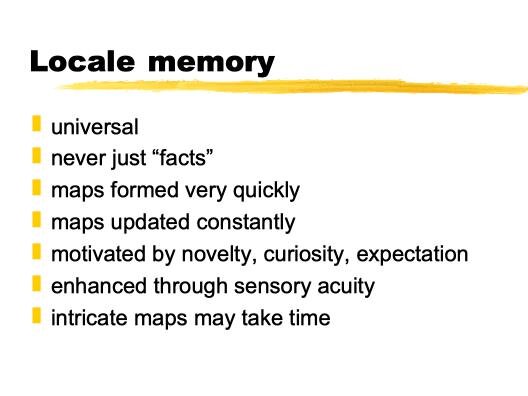

Locale memory is innate and the way we negotiate the world in real life. When you walk into a room that’s new to you, you don’t have to memorize the exit. Your brain has automatically registered the layout of the room. It’s spatial and connected. Learning like this takes longer and is messier, requiring mistakes and correction, but it’s much deeper and more flexible than taxon memory.

So if our classrooms are merely about memorizing facts (Who won the Battle of Vicksburg?), then sure, give the kids a test and if they pass, they pass, and if they fail, they fail. But if we want them to know why the Battle of Vicksburg was fought and what else happened because of it, if we want them to be curious about history and its threads, then we need to provide messier, more recursive ways to explore the information.

This is a pipe dream, of course. Our entire educational system is based on covering the material — and testing those factoids — and the time or resources to explore any of it in meaningful depth is frankly impossible. But when even the business world acknowledges the usefulness of Lichtenbergian Precepts, perhaps the politicians who write our educational policy (and curriculum!) might want to take a look.

They could, naturally, pay me large fees to teach them this. (I used to write about it over on my personal blog.)