I'm back...

/I apologize for the lack of posts for the past week: I was on an actual, honest-to-goodness Viking River Cruise, just like you see on Downton Abbey. Without going into a great deal of boring detail, it is just like the commercials make it look: a relaxing and elegant way to travel up a river. Highly recommended.

Somewhere on the Danube near Krems...

However, the wifi onboard the ship is terrible, which they tell you ahead of time, but hope springs eternal. I had made the decision not to take the laptop — the iPad is lighter — but that was a mistake. I had started out blogging every day over on my personal blog but the technical issues became so tedious that I stopped. (The restaurant manager, Tibor, even teased me every morning about working so hard on vacation.)

But now I'm back and have some things to say about being human and being creative—but I repeat myself.

Here, for example, is St. Peter's Church in Munich:

A lovely example of 18th-century Baroque, isn't it?

Only it's not.

It used to be, but now almost everything you see in Munich was rebuilt only 70 years ago. Rebuilt.

Some of the windows and sculptures had been taken to safety after the war started, but most of what you see in the churches and palaces has been recreated. This is true in Munich, in Nüremburg, and especially in Dresden, although that was not on our trip. Everywhere you go, tour guides will tell you how much of the city was destroyed during the war, and it has all been rebuilt.

This says something to me: the products of our creativity mean something. Great monuments like these cathedrals mean something, something we cannot discard or disregard. The texture of a created/creative space is important enough to preserve.

Now it is unlikely that you or I will ever create something this enduring. Great architectural works are long-term group efforts, after all. But if it's important enough to preserve or to restore, isn't it important enough to create in the first place?

More:

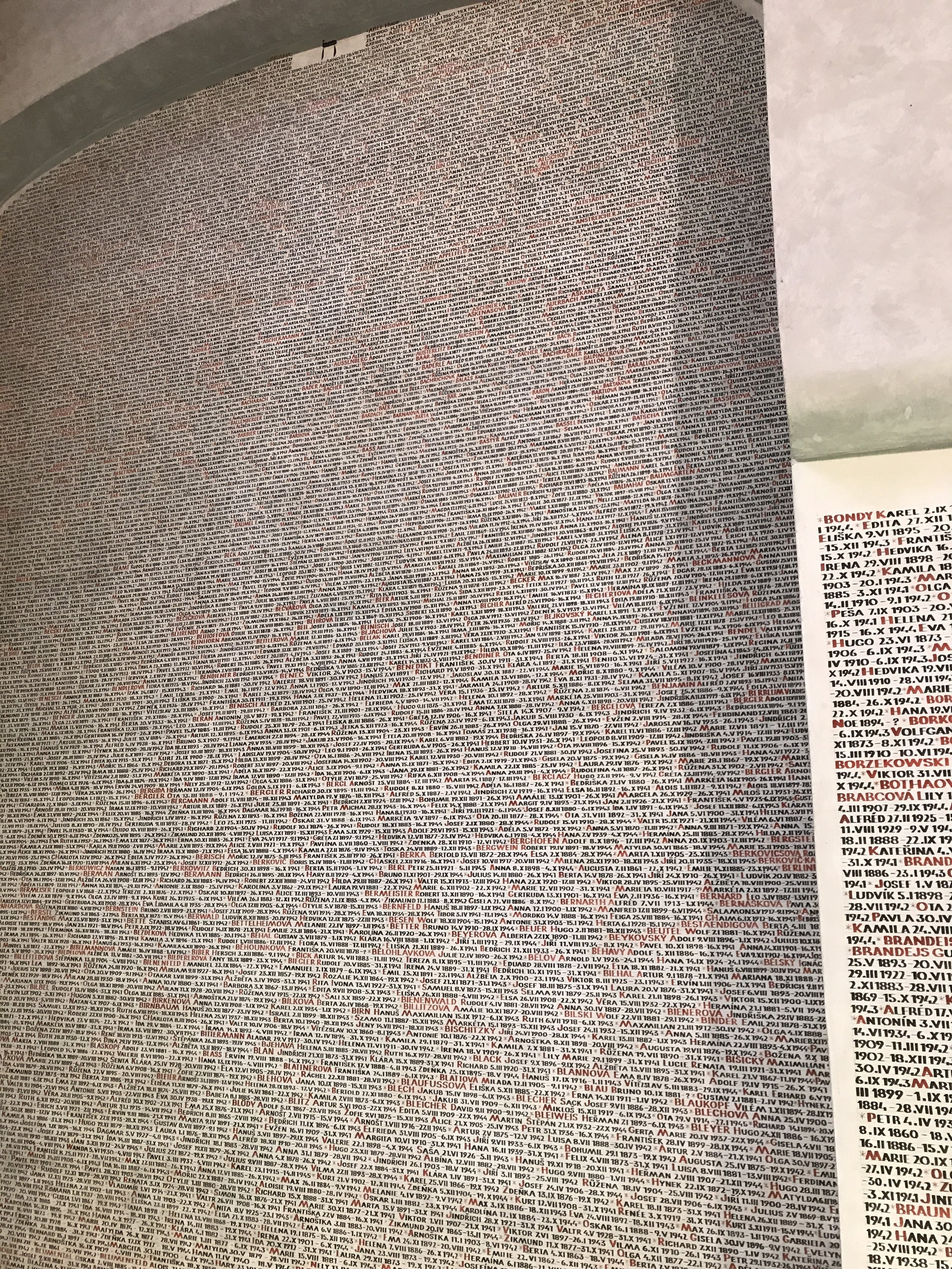

In Prague, we toured the Jewish Quarter, where most of the old synagogues are now part of a museum complex. It is, as you might expect, sobering and heartbreaking.

In the Pinkas Synagogue, for example, the walls of the downstairs sanctuary are covered with the names of the 80,000 Jews deported and killed by the Nazis.

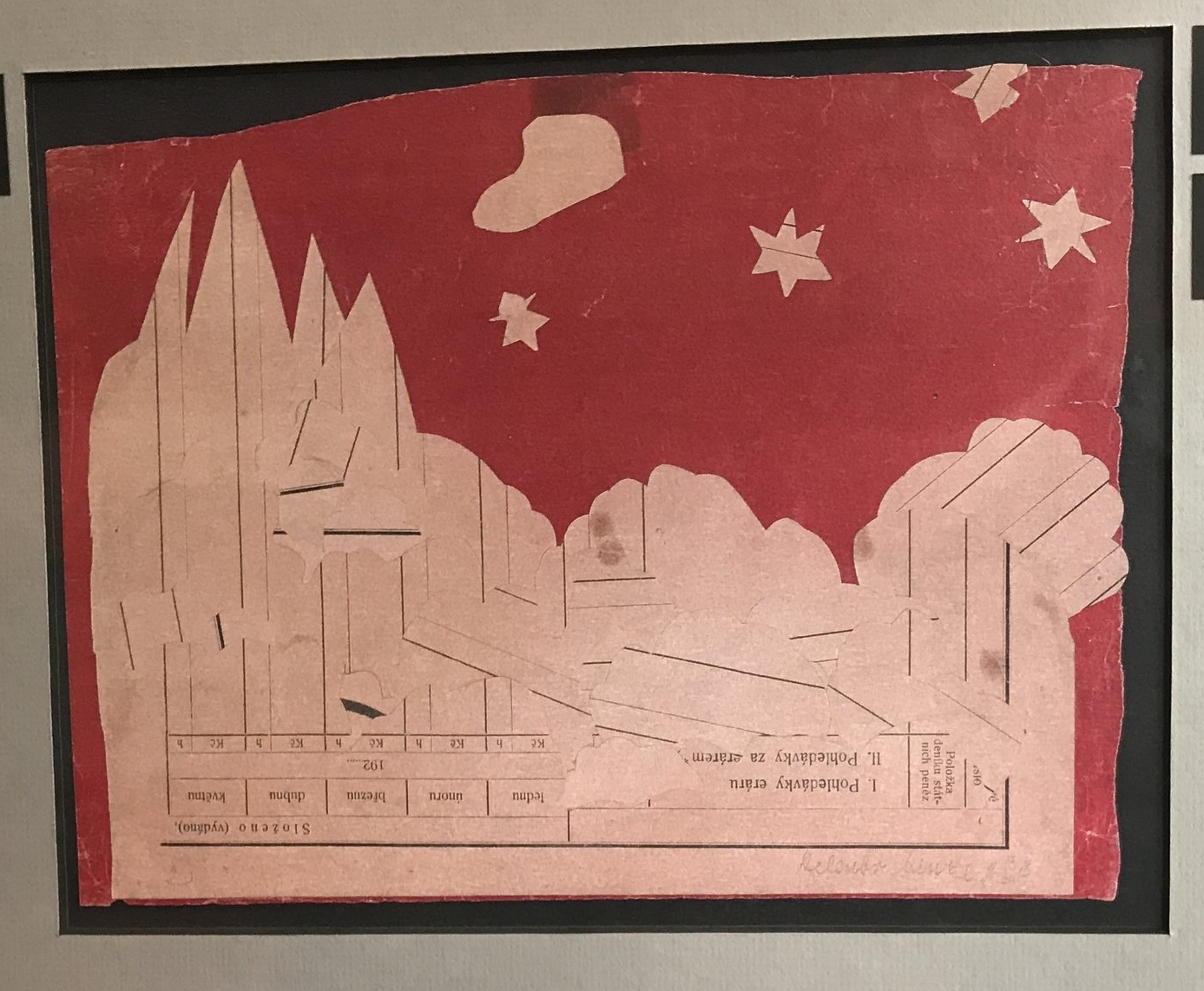

Upstairs, though, is a collection of children's artwork from Terezin, the "model ghetto" which the Nazis used as a kind of Potemkin village to try to convince the Red Cross that they were treating the inmates well. There were concerts, plays, all kinds of civilized signs of life—before the inhabitants were sent onward to the death camps.

One woman, Friedl Dicker-Brandeis, was an artist and educator whose stated goal for her students—even in Terezin—especially in Terezin—was "to rouse the desire towards creative work, to make it a habit, and to teach how to overcome difficulties that are insignificant in comparison with the goal to which you are striving."

Insignificant in comparison.

When she was deported, she left behind a suitcase of 4,500 works created by students in Terezin, most of whom were also deported and killed.

Tell me again why you are not creating? What have you to fear that stops you?

Insignificant in comparison.